A Blog about Scientists With Interesting Hobbies

Interviews from Dr. Lattin’s Scientific Communication for Biologists graduate course at LSU

Ski mountaineering with Michelle Stantial

Michelle Stantial is a Quantitative Ecologist at Four Peaks Environmental Science & Data Solutions in Hood River, Oregon. Michelle was interviewed by Jacob Carignan, a graduate student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Jacob Carignan: How would you describe your research to a 5th grader?

Michelle Stantial: I use math to help understand how we can save endangered species. I think many kids shy away from math, but it can be this really cool tool to help evaluate whether we are doing a good job at saving endangered species.

JC: For anyone who is unfamiliar with it, how does ski mountaineering work?

MS: We’re trying to summit a big mountain. In my case, in the Cascades range, we’re usually talking about big volcanoes. So when you start out, you might hike like normal. Then you put this thing called a “skin” on the bottom of your skis. It kind of looks like a carpet but the fur is directional, so you can glide forward, but they prevent you from sliding backwards. You ski with these along the trail, and once you get to the top, you get to ski all the way back down the mountain.

JC: How did you get started with mountaineering and skiing?

MS: When I was living back east, I always wanted to try backcountry skiing. I always assumed that only professionals could do it. I started doing a little research and in the Adirondacks there was a guide service. So I hired a guide, and went with a couple of friends. The guide taught us how to use all the equipment and took us backcountry skiing. That unlocked all of these other possibilities, and I was like, “well, if I can backcountry ski, then can I get to the top of mountains?”.

JC: Have you had any particularly memorable outings or adventures?

MS: My first ski mountaineering attempt was Mount Shasta in California. It’s a volcano that sits at over 14,000 feet. We tried but didn’t summit it, because we were nervous about the conditions going back down. We turned around about 1000 feet from the summit, but got to ski all the way back down to our camp!

JC: How do you separate time outdoors in your role as a professional from when you are just trying to have fun?

MS: I didn’t really start backcountry skiing or ski mountaineering until my field work started to dwindle, and I didn’t make that connection until just now when you asked that question! Maybe the lack of field work has pushed me towards more adventures in my personal life. You have to think on your feet and react to different situations, but you also need a plan, so there are a lot of similarities!

JC: Do you have any advice for anyone interested in mountaineering or skiing, or just going outdoors in general more?

MS: Start small and don’t be intimidated, because any hobby can be as big or small as you make it. You have to be OK with starting fresh and being new at something. On my first backcountry trip, I rented gear and went with a guide. I didn’t go big right away! Start small, and if you like it, then don’t give up. The key is finding community. If you have a community of people who are supportive and kind, then you can take your time and you can thrive.

Michelle banding a Piping Plover chick for her PhD dissertation research. Photo courtesy of Michelle Stantial.

Michelle and a friend sitting under the moonlight on the side of Mount Shasta. They started their climb that morning at 3 am! Photo courtesy of Michelle Stantial.

Michelle attends a crevasse rescue practice session with some friends in Yosemite National Park. Photo courtesy of Michelle Stantial.

Show Choir with Beth MacDougall-Shackleton

Beth MacDougall-Shackleton is an Associate Professor in the Department of Biology at Western University in Ontario, Canada. She was interviewed by Z Martin, a PhD student at LSU, about her show choir hobby. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Z Martin: How would you describe your science to a 5th grader?

Beth MacDougall-Shackleton: My research asks how birds choose mates that help them produce healthy offspring; partners or mates that have immune genes that work well with their own and that help them resist disease.

ZM: How long have you been participating in choirs?

BMS: Since 2019. We did all sorts of things to keep the choir together [through the pandemic], like practicing at a giant chicken farm where we could stand six feet apart from each other with all these chickens running around us! It was a whole thing, keeping the music going during the heyday of COVID.

ZM: What sort of choir are we talking about?

BMS: We are a show choir, so it's not affiliated with a church or school or anything. It's just people who really enjoy Broadway music, and so we do all Broadway or West End music. We have choreographed dance routines, so it's very fun for Broadway fans.

ZM: How often do you practice?

BMS: We practice as a group every week for about two hours of vocals and one hour of dancing. I probably practice a few times a week, just on my own.

ZM: Do you have a space that you practice in?

BMS: I take over my whole house! I sing the alto part, so it's not the melody, it's the harmonizing part. It's always very entertaining for my family to hear me working on the harmonies.

ZM: How did you find your show choir group?

BMS: Through dog-walking! I was walking my dogs in the park and I ran into another woman who turned out to be a neighbor of mine, and I was saying how I was going to Broadway the next month and how much I loved musical theater. She said, "I'm in a show choir. You should audition!" That's how I learned about it.

ZM: Is there a particular show that you have done that was particularly special to you?

BMS: We did a couple numbers from Six: The Musical. I got all my friends and family to come out and see me being Anne of Cleves! That was great.

ZM: Do you find that your work with songbirds ties in with your love of singing?

BMS: I've been studying songbirds and birdsong forever, and realize now how challenging it is to be singing and bang-on consistent every time, at the same time as you're dancing around and not tripping over the person next to you. It makes me respect songbirds even more!

ZM: Thank you so much for your time!

BMS: It's absolutely my pleasure! I think a lot of times, scientists are hesitant about having hobbies and worried about taking time away from the lab or from writing papers, but a lot of things that make somebody a good performer also make them a good scientist. I feel it's been very reinforcing to my day job to have a side interest and work as part of a team with other people.

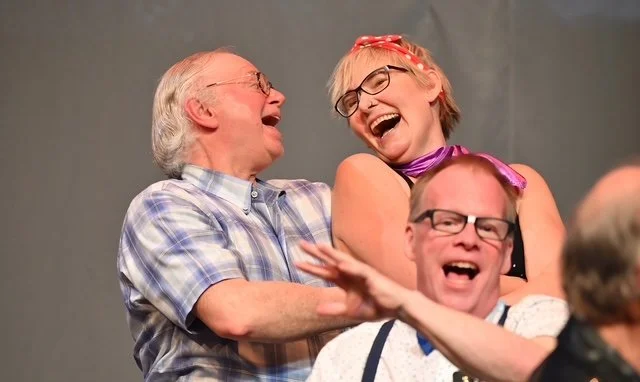

Beth MacDougall-Shackleton and the Silver Spotlight Players performing “Shakin’ at the High School Hop” from Grease: The Musical. Photo courtesy of Beth MacDougall-Shackleton.

Beth MacDougall-Shackleton (as Anne of Cleves) and the Voices of Broadway performing “Ex-Wives” from Six: The Musical. Photo courtesy of Beth MacDougall-Shackleton.

Beth MacDougall-Shackleton and the Silver Spotlight Players performing “We Go Together” from Grease: The Musical. Photo courtesy of Beth MacDougall-Shackleton.

Role playing games & miniature painting with Quinn McCallum

Quinn McCallum is a PhD candidate in the Mason Lab at the Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science. Quinn was interviewed by Amanda Harvey, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Amanda Harvey: How would you describe your research to a 5th grader?

Quinn McCallum: I study how populations of birds differ in their genetics across the Andes Mountains. I'm interested in birds with different ecological traits, diets, and habitat preferences and how that affects how much they move across the landscape and exchange DNA between different populations.

AH: When did you start playing tabletop role-playing games and how did that evolve into painting miniatures?

QM: I was a very nerdy kid, and my mom got the Dungeons & Dragons 3.5 edition starter box at a thrift store for me and my brother. Around the same time, my friends were getting into this game called Warhammer, and both of those games use miniatures. Over the pandemic, I had a group of friends who played tabletop role-playing games, and they started getting into a game that was more miniatures focused, and they got me back into it.

AH: What has been your favorite miniature to paint and what campaign storyline did it fit into?

QM: My favorite miniature I haven't used in a campaign yet. It's very fragile because I painted it as a display piece for a painting competition, but I do have an idea for an adventure for him in my next campaign! It's this frog man with a butcher's knife and a lantern on a bamboo pole, and I've made all of these little bamboo stalks on his base out of toothpicks and stuff.

AH: Do you think your science inspires the storylines and the tabletop role-playing games you run?

QM: Definitely! In my current campaign, the players are traveling across a desert planet getting samples of a fungus for their bosses who are a bunch of scientists, so they can build fungal technologies with them. I have a mycologist in my game who works on the genetics of fungi, and another player who is an ornithologist in population genetics. It has actually led to some problems, because this campaign wasn't written by biologists, so there have been some things where they are like, “that doesn't make a lot of sense”! I have to come up on the fly with a reason why it makes sense to somebody who actually knows about genetics.

AH: What do you think attracts you to tabletop role-playing games and miniature painting?

QM: For tabletop role-playing games, it is partly the adventure and the escapist idea of getting into a fantasy world, and increasingly, it's about getting around a table with a group of people that I like and making each other laugh while coming up with cool stories together. With painting miniatures, it's a very solitary thing, but then I get to bring out miniatures that I've painted and watch people go, “That's so cool!” So it's really the social element to both hobbies that I love.

AH: How important do you think it is for scientists to have a hobby?

QM: It's very important, because we're all people, and we're not one dimensional. You can't just be doing and thinking about science all the time. You're going to get burnt out, so you need some sort of release. You need something else going on to focus your brain on so that you can come back to work refreshed... it keeps the excitement alive, for me at least. I can't just think about one thing constantly.

Quinn working on painting a miniature. (Photo credit: Amanda Harvey).

Quinn’s favorite miniature that he has painted. (Photo credit: Amanda Harvey).

A display case shelf with miniatures painted by Quinn. (Photo credit: Amanda Harvey).

Rock climbing with Kelton McMahon

Kelton McMahon is an Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island. He was interviewed by Yasodha Gamage, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Yasodha Gamage: How would you describe your science to a 5th grader?

Kelton McMahon: My research group is interested in ocean food webs. We're trying to understand who eats whom in the ocean and where animals go to find their food. We're especially curious about how things like climate change, environmental shifts, and human interactions with the ocean might alter those relationships.

YG: What originally drew you to rock climbing, and how did you get started?

KM: I was a very athletic and energetic kid, and my summers were always filled with sports camps. One summer, when I was about 10, one of my camps got canceled. My parents scrambled to find something to fill the time and came across an intro to rock climbing camp at Connecticut College, a small liberal arts college nearby. It was taught by Dave Fasulo, a well-known climber in New England who wrote the Falcon Self-Rescue Guide and put up a bunch of first ascents in the region. I was a tall, skinny kid who loved climbing trees and scrambling on rocks, so I thought it sounded fun. I took the course and fell in love with it. I went back the next year as a teaching assistant, got better, and Dave kind of took me under his wing. We started climbing together, and he taught me everything. We traveled all around the Northeast. That summer camp turned into a lifelong passion. Now it’s been 32 years! I started competing [in rock climbing competitions] when I was about 14, and by 17 I had sponsorships. I competed for about 10 years after that. In my late 20s, I stopped competing because it became hard to balance travel for climbing and research. At that point, climbing as a career wasn’t really sustainable.

YG: What keeps you passionate about it after so many years?

KM: I have two answers. The broader one is that I love the combination of mental and physical challenges. Physically, it's a full-body workout. You're twisting, pulling, using every muscle. Mentally, it's problem-solving puzzles and sequences. It’s very creative, and I find it incredibly stimulating. More recently, my 4.5 year-old daughter has gotten into climbing. Watching her get excited about it has been a proud dad moment for me.

YG: How has your approach to climbing changed now that you sometimes share the experience with your 4 year-old?

KM: This is going to get deep. I've always been incredibly competitive. I tend to tie my self-worth to how well I do things, and I definitely don’t want to pass that mindset on to my daughter. I want her to feel good about herself no matter what. So, it's been an important exercise for me to focus on sharing the positive aspects of climbing without pressure or perfectionism. I want her to feel powerful, creative, and valuable, no matter the outcome.

YG: What are some of the biggest mental or physical challenges you've faced while climbing, and how did you overcome them?

KM: When I was younger and competing nationally and internationally, the biggest challenge was mentality. I put a lot of pressure on myself to win, which wasn’t always productive. I eventually saw a sports psychologist, which helped me redirect that energy in healthier ways. Now, in my 40s and as a parent of two, I’m not as strong or flexible. I don’t have time for the same training. So it’s become more about setting a good example for my daughter than pushing myself to the limit. Her presence reminds me what really matters, and it's helped me find joy in climbing again.

YG: Has rock climbing taught you anything unexpected about yourself or how you approach problems?

KM: Absolutely. One of the biggest lessons is about dealing with setbacks. Injuries are common. I've snapped tendons in my hands, which meant long recovery periods. For someone active like me, that’s tough. But those moments taught me patience. I learned how to stay engaged with the community and the sport even when I couldn't climb. That mindset of thoughtful, patient engagement has carried over into every part of my life.

YG: Where is your dream place to go rock climbing either for yourself or with your family?

KM: Two places come to mind. I’d love to take my family to Thailand. I’ve been before, and it’s magical, amazing climbing, kind people, and fantastic food. My kids are adventurous eaters, so I think they'd love it. The second is Spain. I’ve never been, but it has incredible climbing. Some of the cliffs go over the ocean, and people free solo there with no ropes, you just fall into the water. I speak Spanish, so spending time there would be a dream.

YG: What advice would you give to someone curious about trying rock climbing for the first time?

KM: Learn safety along with technique. The more you understand how to climb safely, the more it opens up adventures. I was lucky to be trained by someone who wrote the book on safe climbing! Also, trust your feet. That’s a classic saying in climbing. People focus on their hands because they feel more secure, but real power and control come from your feet and legs.

YG: Is there anything else you’d like to share about your hobby?

KM: One of the things I love most about the climbing community is how activist-minded it is. Organizations like the Access Fund and Climbing for Change do amazing work to protect natural resources and make climbing more inclusive. Climbers really care about the environment, and that advocacy is something I value deeply. I think it’s important that people see how connected the climbing world is to broader environmental efforts.

Kelton and his students conducting coral reef monitoring in the Red Sea. Photo credit: Simon Thorrold.

Kelton holding a sediment core taken from a sedimentary pond of a king penguin colony in South Georgia Island. Photo credit: Mike Polito.

Kelton sport climbing in Thailand as an Assistant Professor. Photo credit: Mac McMahon.

Kelton and his 4.5 year old daughter Willow climbing at a rock climbing gym in Rhode Island. Photo credit: Molly Sinkelman.

Kelton sport climbing in Thailand as an Assistant Professor. Photo credit: Mac McMahon

Kelton and his mom climbing together at Farley Ledge, Massachusetts when Kelton was in college. Photo Credit: Mac McMahon.

Sailing with Katharina Hoff

Dr. Katharina Hoff is a Privatdozentin (University Lecturer) in Bioinformatics at the University of Greifswald. Katharina was interviewed by Jackson Ferber, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Jackson Ferber: How would you describe your research to a 5th grader?

Katharina Hoff: Can I describe it to a 3rd grader? My daughter is in 3rd grade.

JF: Yeah, even better.

KH: All living beings on the planet have some heritable information that determines the color of your eyes, the color of your hair, your height, and so on. This information is stored in a place called the genome. My work analyzes the genome, finding out where the information is stored. We make software that can basically read the genome and divide it into different parts, some that are protein coding, and some that are not. Proteins make up a big part of the material that determines how you look. That's what I usually explain to my daughter.

JF: How did you get into sailing?

KH: It's kind of an inherited hobby. My grandfather had a boat called the Naviculum, and my grandparents would take me and my cousins on sailing trips. My father also liked sailing, so he would take us out on boats. [At one point], I had the choice of getting a driver’s license for a moped or a sailboat, and of course I went for the boat.

JF: Are you into racing?

KH: I'm more the cruising type. I did one race with my first boat, a very sturdy North Sea boat I bought as a student. I lived in Göttingen [a university town in Germany]. It's far from the sea, and the only place to sail is a small lake, so I put the boat on it. I participated in a sailing race and finished two hours later than everyone else. I'm not into racing. I like to cruise.

JF: Have you gone on any long destination trips?

KH: The furthest I've been sailing is from Sesimbra to Porto, on the Atlantic coast of Portugal. But that's unusual for me. That boat, called the Sea Monster, wasn't a new boat, and the engine broke.

JF: How did you handle the engine breaking?

KH: When we figured out we couldn’t start it again, we sailed as close as we could to Porto, and then radioed the port and asked to enter under sails, which is normally forbidden. They said no, and the Coast Guard towed us.

JF: Do you have multiple boats?

KH: I have one boat. My father bought it about 14 years ago in the Netherlands and brought it to where he lived, on the Rhine River. Then he repeatedly got skin cancer. He figured he should get out of the sun, and eventually he was like, "Oh, let's give the boat to the kid." So, I got a 10 meter yacht for free.

JF: What is the most beautiful place you have either anchored or sailed through?

KH: I'll give you something local. I got my boat the summer I was pregnant, and since then, I have not left Germany with my boat. There is a beautiful island [in the Baltic Sea] called Hiddensee that I really like. The University has a research station on that island, so we go there for sailing and work.

JF: Do you have a sailing dream destination?

KH: I would love to sail around the world and see amazing islands like the Galapagos and the Caribbean islands. But honestly, I don't think it will happen. My husband doesn't like sailing. Unless I want to leave him, which I don't want to do!

JF: Is there a particular sailing moment you still think about?

KH: The funniest moment was with my dad and family. We were all on the boat, sailing from the Rhine River down to the North Sea. When you go down the Rhine, you can’t sail, but we had the mast up. My dad had picked [a port] in a bay behind a bridge. The height of the bridge is indicated on the map, and we were close to not fitting through, but it looked like it would work. We went very slowly, very carefully, because we weren’t 100% sure about our calculations, and heard a big bang! We all panicked, and started backing up. My dad screamed, "They're sending electricity from the bridge," and we were all like, what? Apparently, while focusing on the bridge, my dad pulled something and a life vest inflated, and that's why everything was vibrating for him. We didn't collide with anything, but he was sure we had hit the bridge and it was sending down electricity.

JF: Do you ever find parallels between sailing and your work?

KH: I need hobbies because science is too frustrating. Reviewers see things differently, or sometimes you don't have time to finish things. If you have any success in science, that means half the time you're failing! But I do connect my work with sailing. Last summer, I took a student [on my boat] to collect water samples. Sometimes we have work meetings on Hiddensee and depending on how close we are to not having enough beds, I may take my boat.

A selfie of Katharina on her boat. Photo courtesy of Katharina Hoff.

Katharina and her daughter, Hanna, sailing. Photo courtesy of Mario Stanke.

Katharina and her daughter sailing. Photo courtesy of Mario Stanke.

Typical view on Katharina's boat. Photo courtesy of Katharina Hoff.

Katharina's dog sailing. Photo courtesy of Katharina Hoff.

Singing and Dancing with Kristina Smiley

Kristina Smiley is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Michigan. Kristina was interviewed by Kimia Nourozi, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kimia Nourozi: You enjoy singing and dancing. Do you find any connection between those hobbies and your scientific work?

Kristina Smiley: During my second postdoc, I started shifting my research interests into auditory neuroscience, and that's when I started singing and dancing as a hobby. It was interesting to be learning about how the brain processes sound and then learn about sound in a different way, producing my own sound, and then with dancing, matching my body’s movements to the rhythm of the sound. So there were these strange parallels where my research ended up mirroring things I was learning about singing and dancing. I’ve also noticed that that going to karaoke really helped me with public speaking. I always liked giving talks, but learning how to sing teaches you how to relax while you're projecting. And that's what you need to do when you're giving a talk: if you're not relaxed, your voice gets strained.

KN: What inspires you to sing?

KS: It was my childhood dream job! I always wanted to be a singer, but I never really pursued it. And something just clicked one day, where I was like, I should just start. I didn’t know how to teach myself to sing better, so I decided to find an instructor. It's just something I do for enjoyment that’s really different from my day-to-day work-life.

KN: What genre of music are you interested in?

KS: I like a lot of genres, but the more I got into singing, my instructor told me I’d probably really enjoy jazz singing. I've gotten really into both instrumental jazz and woman jazz singers.

KN: Do you have a dance instructor?

KS: I go to classes and social dances and learn about dancing there.

KN: Do you have a go-to karaoke song, or a favorite style of dance?

KS: I have two. When I started singing, it coincided with me meeting a group of friends at karaoke almost every week. I would always sing “La Isla Bonita” by Madonna because that was one of the first songs I learned in my singing lessons. My other go-to is Tracy Chapman and “Give Me One Reason” because I just really love singing that song. As for dance, I like Latin dance – mainly bachata and salsa.

KN: Has music or dance helped you cope with the challenges of being in academia?

KS: I think that's probably one the biggest things I’ve gotten out of it. Academia is such a mental job - you're in your head all day, thinking and concentrating and working through problems. When you sing or dance, you get much more in your body. Having a singing lesson, or going dancing, makes me feel so refreshed. I think it’s better than any nap I could ever take!

KN: If you could collaborate on a musical number or performance, what would it be like? And with who?

KS: I think doing musical theater performances would be fun, and then you can combine dancing and singing. And, about who I would want to collaborate with: I will never ever be on her level, but I love Ariana Grande's voice. I think she is truly talented. You can just, like, drop me into Wicked with Ariana Grande!

KN: What would your advice be for those who are interested in science and singing, like me?

KS: Singing is a lot more accessible than people may think. I think a lot of people find it intimidating, or maybe they feel too shy, or like they don't have that natural talent, but singing lessons are [a good way to] practice relaxing your body and letting go. That's one of the first things to learn – how to relax your muscles. It’s also training your ear to hear certain sounds, and training your body to produce certain sounds. Everybody who has a voice can sing. One of the big takeaways is that anyone can do it; we are all born with this natural ability to sing.

KN: The beauty of singing is that everyone can sing.

KS: It was sort of surprising to me, because singing lessons were so different from what I thought they were going to be. And, I just say, why not try it? My instruction was all virtual. You can have effective singing lessons online – sometimes it is 30 minutes a week, sometimes it is an hour a week. You might feel so busy, but, if you think about it, 30 minutes out of my whole week, that's not a lot.

Kristina Smiley studies the evolution, neurobiology, and physiology of parenting behavior as an Assistant Professor at the University of Michigan. Photo courtesy of Kristina Smiley.

Kristina singing karaoke at a local gathering spot, the Majestic, in Northampton, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy of Kristina Smiley.

A video of Kristina salsa dancing. Video courtesy of Kristina Smiley.

Playing the violin with Tal Ohana

Tal Ohana is a PhD student in the Quantum Optics Group at the Weizmann Institute of Science. Tal was interviewed by Rujuta Vaidya, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Rujuta Vaidya: How would you describe your research to a 5th grader?

Tal Ohana: In my lab, we are trying to build a new, faster computer – the quantum computer. The quantum computer will be able to handle many complicated tasks at a time, and it will do them faster than our current computers.

RV: What got you interested in violin?

TO: I started playing when I was 7 years old, and for a while I even considered becoming a professional violinist. I also enjoy playing with other people and ended up befriending many researchers in our institute who play various instruments. Connecting with these talented artists made me realize that what we really needed was a group to organize our practice sessions and showcase our music. So I founded the Weizmann Orchestra along with a friend of mine. Having that organizational structure has helped us all get together to practice our craft and it has been such a rewarding experience to learn and grow together as artists. As of now, we are a team of 30 players and a conductor. We’ve also been able to secure a grant to help sustain our little group and organize concerts for folks in the institute. Currently, we are practicing hard for our upcoming summer concert!

RV: What do you enjoy most about your hobby?

TO: I enjoy having these moments when you are “in the zone”: your heartbeat slows down, and you feel calm, kind of like meditation. It helps me concentrate better too. I also enjoy learning new things and the whole process of figuring it out. It feels so rewarding to take on a new, challenging piece of music and practice it until I get the hang of it.

RV: Are there any composers that you particularly love?

TO: My favorite classical piece is the Violin Concerto in E Minor, Op. 64 of Mendelssohn. The first time I heard it I had tears in my eyes. I was still learning how to play violin back then, but I knew in that moment that I wanted to learn that piece. After years and years of practicing, it has become one of my favorite pieces to play. I also like modern music and am constantly trying to listen to new genres that I haven’t heard before.

RV: Do you have any funny or memorable stories from your performances?

TO: Two of my music instructors were a Russian couple, and they talked to each other in Russian during my lessons. I ended up picking up some Russian too – I wasn’t fluent enough to speak it, but I understood it pretty well. We were practicing for an upcoming concert and as we were leaving, my instructors and I discussed the concert date and time and our outfits [in Russian]. Cut to the next day: I arrived at the concert venue all dressed up for the big event – only to find it empty except for security personnel! The security guards were kind enough to tell me that I had gotten the dates wrong, and the concert was tomorrow. Turns out my Russian wasn’t as great as my instructors thought!

RV: If you could meet one famous historical scientist, who would it be?

TO: I wish I could meet Albert Einstein and his violin Lina. I would ask him how he managed to combine his love for music with his scientific pursuits and whether any of his brilliant ideas came to him while he was playing his violin!

Tal playing violin in her hometown of Arad, in Israel. Photo courtesy of Tal Ohana.

Tal in an impromptu jamming session with her friends. Photo courtesy of Tal Ohana.

Tal with the Weizmann Orchestra group that she co-founded. Photo courtesy of Tal Ohana.

Painting with Pablo Moreno Garcia

Pablo Moreno Garcia is a postdoctoral researcher in the Li Lab in the Department of Biological Sciences at Louisiana State University. This interview is about Pablo’s painting hobby. Pablo was interviewed by Rohit Jha, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Rohit Jha: How would you describe your research to a fifth grader?

Pablo Moreno Garcia: I study how pollinators like bees and butterflies interact with plants. For example, temperature changes and prescribed fire management can change plant communities, so I study how changes in plant communities affect pollinator communities and the interactions between plants and pollinators.

RJ: Do you remember your first painting?

PMG: I have been drawing and sketching since a very young age. I did my first oil painting when I was nine years old.

RJ: Why do you prefer oil painting to other types of art?

PMG: I love oil-based painting because it takes more time. It really requires patience compared to watercolors, which are faster and you must work faster because they dry quickly. With watercolors, you must manage your time well and be sure of what you want to do. Oil paintings are different. They allow you to make more mistakes. It takes longer to dry. You can work on a portion of it, let it dry, and in the meantime you can think about what you want to do next.

RJ: How did you get into painting?

PMG: I started with drawings. I did a lot of them! I would create stories and little characters and things like that. But then when I was around eight or nine years old, we went to a small regional art fair, and that's where I met my painting professor. I still remember that she was sitting in a small booth surrounded by her paintings, which were beautiful. She used to smoke a lot and she was smoking then. She and her paintings were surrounded by the smoke, and it gave a whole bohemian artist impression. My parents knew her, so they talked to her about my interest in painting and enrolling in classes. That is when I started going to classes, which I continued during my bachelor’s degree. There was even a question about whether I would go for an ecology-based or an artistic degree, because of my love for painting.

RJ: Can you talk about one of your paintings that is particularly special for you?

PMG: The one which is most special to me is not an oil-based painting, it's a crayon painting. It is based on a painting by a Spanish painter, Sorolla. In the original painting, there is a woman with a child in an orange field. I changed some elements of it so that it portrays my grandma and my little cousin. I gave that painting to my grandma and she cherishes it a lot. She says how much she loves that painting every time I visit her. It brings me so much joy.

RJ: Do you think your painting in some way inspires the science you do, or vice versa?

PMG: I think that painting is an activity that comes from appreciating nature. When I do my paintings or observe other paintings - especially landscapes - I love to imagine how that [ecological] system works and think about the biotic and abiotic components of that system. I think it acts like a two-way feedback mechanism. One the one hand, your painting inspires the research you do, and your research subjects inspire what you paint.

RJ: How important do you think it is important for scientists to have a hobby?

PMG: I really think they should have one. There are so many things outside of work that are worth exploring. Having a more balanced life where you can have hobbies and time with friends and family along with your job gives you more of a sense of fulfillment and greater happiness. It is also helpful with a job that is really demanding and can be very hard. Sometimes you may have papers rejected or results that don't turn out as you wanted and that can really affect you. In those situations, having other things in your life that you can rely on can be super helpful.

Pablo doing fieldwork with pollinator sampling equipment. Photo courtesy of Pablo Moreno Garcia.

One of Pablo’s favorite paintings, which he gifted to his grandmother. Photo courtesy of Pablo Moreno Garcia.

Another of Pablo’s favorite paintings, of the famous Brandenburg gate in Berlin, Germany. Photo courtesy of Pablo Moreno Garcia.

Dog competitions with Kale Rougeau

Kale Rougeau is a Master’s student in the Elderd Lab in the Department of Biological Sciences at Louisiana State University. This article is about Kale’s hobby of participating in dog competitions. Kale was interviewed by Nathaniel Haulk, a Master’s student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Nathaniel Haulk: How would you describe your research to a 5th grader?

Kale Rougeau: We study caterpillars and what makes them sick in order to help farmers and scientists. A lot of caterpillars are bad, and we need to know how to stop them from eating crops like corn and rice.

NH: When did you adopt your dogs? How did you choose those two specifically?

KR: I wanted to get a Dalmatian my whole life. When I was 21, I found a lady in Texas that had a litter available and contacted her. I researched which one would best fit the Dalmatian standard, and it was a dog named Jake. I got him in 2018 when he was eight weeks old. From then up until the beginning of 2019, I looked at more breeders that matched what I would want for a dog, and eventually I found a breeder in Florida. She had a litter that was born August 2019, and she and I worked together for the next eight weeks to select a puppy. Based on temperament, structure, and the other features I wanted, I selected June.

NH: When did you first become interested in competing?

KR: That was something I wanted to do my whole life. Growing up, I was always around dogs and livestock. Dog shows were my favorite of the livestock shows, and I was interested in agility, which is racing around an obstacle course, and in a few other sports that were televised. When I was in high school, my family acquired a few Husky mixes, and I started going to agility classes with one of them, Lucy. I found the agility classes enjoyable and then picked up obedience classes. Once I got June, I had a dog that could do it more competitively, and that made me want to compete in more sports.

NH: What was your first competition with the Huskies? And what was your first competition with the Dalmatians?

KR: With Lucy, my first competition was a barn hunt competition, where dogs find rats in hay bales. She did really well, and that was a really fun and encouraging start. June's first sport event was FastCAT, a 100-yard dash for dogs, and she did not do well. She had no idea what to do! Now, it's actually her favorite sport, and she has a personal best speed of 27.16 MPH. June’s actual first competition was when she was a four-month-old puppy, and she did a conformation show. These tend to be the typical dog shows where they compare temperament, expression, movement, all of that. For the first competition, she did really well and won best puppy among the other Dalmatians.

NH: So far, what has been your favorite event?

KR: I would say agility. That was something that I always was interested in, and it's the very first class I took. It's also one of the hardest events and is a long term and difficult investment. June has her agility course test title, but even with both dogs I've done ability trials with, I am still working on getting actual trial titles.

NH: Are there any competitions you'd like to enter in the future or are there any milestones you want to reach in the future?

KR: In May, I have a rally trial, and beyond that, there's a barn hunt trial in July. In the grander scope, I really want to go to the Dalmatian Club of America National Specialty. That’s the yearly national competition where all Dalmatian owners who are in the club come together and compete, and it’s held in a different state every year. I'd also like to attend Westminster and the American Kennel Club National Championships.

June winning Best of Breed for a 3-point major at an American Kennel Club conformation show. Image courtesy of Kale Rougeau.

June running in a FastCAT 100-yard dash. Her personal best speed is 25 MPH. Image courtesy of Kale Rougeau.

Jake with his Novice Trick Dog and Intermediate title ribbons. Photo courtesy of Kale Rougeau.

June performing in a scent trial. Multiple essential oils are placed around an arena and each dog has to pick out the correct one. Video courtesy of Kale Rougeau.

Woodworking with Jerry Ferris

Jerry Farris is a Distinguished Professor of Environmental Biology at Arkansas State University, and enjoys woodworking in his free time. Jerry was interviewed by Kevin Krajcir, a former graduate student at LSU and current Grants Coordinator for the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kevin Krajcir: How would you describe your science to a 5th grader?

Jerry Farris: I work with [the process of] cleaning water. I study animals that reflect the impact that we have on water. Like a doctor might take your temperature, I take measurements from these animals to determine if they are feeling well.

KK: How long have you been practicing woodworking? What, or who, initially drew you to the hobby?

JF: My father had a shop in our backyard. From him, I learned how to use and take care of the tools. I remember when I was 6 or 7 years old, I would sneak his tools out into the yard! Eventually, I began my own collection of tools. The pieces I make are largely inspired by my passions as a naturalist. While working on my Master’s degree [at Arkansas State University], I realized I could craft birds, invertebrates, and other decoys. My style, however, was largely influenced by an artist. I took a print-making class as an elective in graduate school, and I was always amazed by the work of our professor, Evan Lindquist. When I asked about his inspirations, he told me that prior to becoming an artist he went to school for biology! His insight into both fields has inspired my craft.

KK: Can you describe some of the pieces that you’ve made?

JF: I have six grandchildren, and I recently made them an ark filled with animals. This ark has been the most challenging piece I have ever made, based on its size and the numerous animals I made. It was a bit difficult to hand it over to my grandkids for them play with once I was done! I have also used my skills to craft pieces for scientific societies. I found out that folks really like shorebirds, so I have donated pieces to silent auctions and the funds have been used to raise money for graduate student travel to these conferences. I have also gifted pieces to genuinely nice students who have worked with me, in the lab or elsewhere, as a going-away present. I typically create something based on their scientific interests.

KK: Of all the pieces that you have made, is there one that is particularly special to you?

JF: I value them all, because they represent different periods of my work and different people who I have worked with over the years. I have a carving of a predaceous diving beetle as a piece of office furniture. What makes it special is that I have the names of all the technicians from that project carved into the wood. So it serves a reminder of my time with those folks.

KK: Is there any advice you have for folks wanting to get into woodworking?

JF: Visit every museum when you get the chance to travel anywhere! I love the Smithsonian Institutition and the indigenous cultural museums of the Pacific Northwest. You learn so much about the craft and various styles by seeing others’ works and their processes. Learn what you can from books, magazines, and online resources as well; there is so much available on this topic!

The wooden ark with pairs of animals that Jerry made for his grandchildren. Photo courtesy of Jerry Ferris.

A wooden diving beetle carved with names of different technicians and locations from the associated project. Photo courtesy of Jerry Ferris.

Another of Jerry’s projects, a wooden oryx that he gifted to a former student. Photo courtesy of Jerry Farris.

Rockhounding with Aimee Van Tatenhove

Aimee Van Tatenhove is a PhD Candidate in the Quinney College of Natural Resources at Utah State University and a Science News Reporter for Utah Public Radio. This interview is about her hobbies of rock tumbling and rock and fossil collecting (aka “rockhounding”). Aimee was interviewed by Hirusha Algewattage, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Hirusha Algewattage: How would you describe your research to a 5th grader?

Aimee Van Tatenhove: I study pelicans that nest on an island in the Great Salt Lake, which is this huge salty lake in Utah. I basically study where they like to go, how well they're surviving, and what causes their populations to get bigger or smaller.

HA: When did you first start collecting rocks and fossils as hobbies?

AVT: I've been collecting rocks and fossils most of my life with my family. We all live in rock towns, so we all love to collect rocks and fossils and gems, and I realized how fun it is to go look for shiny things on the ground. I got into rock tumbling specifically in 2020 as a pandemic hobby. I bought a small rock tumbler and got some grit to add to it to make the rocks shiny.

HA: Can you describe the the process of selecting rocks, and how you determine which ones are suitable for collecting and tumbling?

AVT: I first identify rocks based on their physical characteristics. For example, I can tell if a rock is hard or soft, shiny or dull, and if it leaves a mark when rubbed against something. Usually I choose rocks that have a similar hardness to one another, and which are quite hard. I put them together in my rock tumbler and change out the grit as they become shinier. During the tumbling process, I monitor the rocks to ensure that they are tumbling well. If I notice that some rocks are not tumbling well, I replace them with different ones. Ultimately, I aim to select the hardest rocks because they are the ones that will end up the shiniest once the tumbling process is complete.

HR: What is your favorite rock to collect?

AVT: I personally prefer a hard blue-colored metamorphic rock called specular hematite for the tumbling process. It looks great, and has a somewhat metallic color.

HA: Have you found any interesting fossils?

AVT: I have collected at many different sites, and each one has its own unique collection of fossils. There's a fossil site in Idaho that I've frequently visited, which has a lot of interesting fossils. For instance, I have collected trilobites, which are tiny bug-like creatures. Where I live in Utah, I often come across fossils such as crinoids, which are plant-like sea creatures, as well as various types of coral and fish. A couple of summers ago, I participated in a program where you pay to help with an excavation in Montana. We were able to dig up pieces of dinosaurs such as an Allosaurus, which is a huge dinosaur. It was an incredible experience. However, I couldn't keep any fossils of that dinosaur because it was not allowed.

HA: What advice do you have for people that are starting out rockhounding as a hobby?

ATV: If you are thinking about getting into tumbling rocks or collecting rocks and fossils, do your research first. It's important to understand the basics before you start, and you can find a lot of information online, in books, and from other collectors. You should learn about the different types of rocks and fossils, the equipment you'll need, and the techniques involved. Another tip would be to start small when you're just getting started. It can be overwhelming if you try to build a big collection right away, so it's a good idea to begin with just a few rocks or fossils. This will give you a chance to learn more about the specimens that you're interested in and develop your skills over time.

Aimee holding a dinosaur fossil collected in Montana that has been prepared for transport. Photo courtesy of Aimee Van Tatenhove.

Aimee collecting fish fossils with her family near Fossil Butte, Wyoming. Photo courtesy of Aimee Van Tatenhove.

Tumbled amethyst that Aimee collected from the Thunder Bay amethyst mine. Photo courtesy of Aimee Van Tatenhove.

Blue rocks from Wyoming in a rock tumbler drum. Photo courtesy of Aimee Van Tatenhove.

Making Crochet Animals with Amy Panikowski

Amy Panikowski is a freelance scientist in South Africa. This article is about her hobby of making crochet animals. Amy was interviewed by Anjira Sengupta, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Anjira Sengupta: How would you describe your research to a 5th grader?

Amy Panikowski: I wear a lot of different hats when it comes to my research. Professionally, I am a scientist for hire. Some days that can be studying water control, other days I'm studying natural resource management. I also work with rural communities, and some days I'm playing with snakes. I am also an educator. I talk to people about snakes and other reptiles, and why they are important.

AS: How did you get into crocheting animals?

AP: I started around 2018. I went to the University of Florida for graduate school and got my Master’s degree, then I came to South Africa to do research and I met a guy [later husband] there. The entire visa process was too much and that’s when I started to crochet to deal with the stress of going through visas every couple of years. Since the beginning, I wanted to do something more contemporary. Around 2021, our former vet, Dr. Gustav Botha, was moving away. He and his wife were having a second child. I said, “Well, can I make you something?” Gus said, “We have enough blankets, we want a dinosaur.” So I made an Ankylosaurus for them. That was my first crochet animal.

AS: How long does it take you to finish one project?

AP: With my daily schedule, it takes about 2-3 weeks to finish a project. I'm typically a nighttime and weekend crocheter, as other things take up my time - freelancing, rescue and rehabilitation [of wildlife], conservation education, etc. Bigger projects take longer. I am one of those people who tends to have multiple projects going simultaneously.

AS: What are some of your favorite pieces you’ve crocheted?

AP: I made my nephew a chameleon and a frog. My niece likes horses and fish, so I made her little versions of each. My mom loves the beach, I made her a little sea turtle. In 2016, my dad came to South Africa and he just fell in love with the rhinos. So I made him a little rhino. I think those are my some of my favorites.

AS: What would you tell a person who is planning to start crocheting? Can you suggest some resources that might help a beginner?

AP: I'm pretty much self-taught. If you're like me who's a visual learner, YouTube is a great tool. But if you've got a friend that has been crocheting for a while, you can work with that individual side by side. My friend Angie [Redinger] taught me how to read crochet patterns. She's the one I went to when I had to learn how to read and understand that Ankylosaurus pattern!

AS: Do you feel crocheting helps with your conservation work?

AP: All that love for conservation just manifests itself in different ways throughout my life. When I'm working on a [crochet] piece, and I'm counting the stitches, sometimes other conservation things pop up in my head, or things I need to work on, or remember later. But it also gives me a break when I'm in a deep work mode. It gives a bit of time for my brain to relax while at the same time still being productive. I do a lot of work with snakes here. I have to deal with people who kill snakes. I see a lot of dead snakes during the summertime, almost on a daily basis. I spend an enormous amount of time and effort getting people not to do it. It can cause a lot of burnout. Crocheting really helps me on those days.

AS: Do you think having a hobby beside science helps scientists?

AP: Oh yeah, you have to have a hobby. I actually think that there should be more time, especially in grad school, for artistic outlets. I think art is really important for people, even very sciencey people. When I grew up, I was a dancer and I danced all the way through college. We all need something that gives our minds a break, and a different perspective really helps with your work. I hope my crochet animals [on Instagram and Twitter] help people understand the importance of natural organisms, because I really would like people to care about nature.

Amy doing education work with a black mamba snake. Photo courtesy of Amy Panikowski.

Ankylosaurus and her friends, some of the first crochet animals Amy made. Photo courtesy of Amy Panikowski.

The sea turtle Amy made for her mom. Photo courtesy of Amy Panikowski.

The rhino Amy made for her dad. Photo courtesy of Amy Panikowski.

An owl crochet animal. Photo courtesy of Amy Panikowski.

Fostering Cats and Kittens with Carrie Barker

Dr. Carrie Barker is currently a research associate at the Shirley C. Tucker Herbarium at Louisiana State University. Carrie was interviewed by Aislinn Mumford, a PhD student at LSU.

Aislinn Mumford: How would you describe your science to a 5th grader?

Carrie Barker: I study plants, how they got to where they are growing, and why certain species grow in some areas where other species do not.

AM: How did you become interested in fostering cats?

CB: I started off volunteering at a local animal shelter. I first started walking dogs, then cleaning cages. I’d always wanted to foster, but at that time, I was traveling a lot, so it wasn't feasible. Then the pandemic happened. I wasn’t traveling then, so I was able to start fostering. I really fell in love with it, so I made it a point to continue doing it.

AM: What is the fostering process like? If someone were interested in fostering, how would they go about doing it?

CB: Usually a shelter will have either an email or a link that you can use to sign up. Each shelter will give you some basic training on how to become a foster. After that, as cats come in, they will reach out to their network of fosters. Sometimes they do that through an email listserv. Cat Haven [in Baton Rouge, LA], the shelter I foster at, has a Facebook group, and anytime they have cats or kittens that need to be fostered, they'll just post, and whoever is first to say, “I can take those kittens” will take them. The length of time that you are required to foster for the cats or kittens depends. For kittens, you usually foster until they are eight weeks old and two pounds. If they are adult cats, there may be particular reasons why they need to be fostered. It may be that they have health problems, or that the shelter is having a hard time keeping up with so many cats, or they may need more socialization if they were a stray, so the length of time can vary. It can be up to the discretion of the person fostering. One time I fostered a feral cat for four months because she needed more socialization.

AM: Do you have a favorite memory from fostering?

CB: One time I read a Facebook post a little too quickly. I thought it said they needed a foster for three five-week-old kittens, and it actually said five three-week-old kittens! That was my first time fostering kittens and they had to be bottle fed. You have to bottle feed them every three hours and wake up in the middle of the night to feed them. Luckily, this was during this summer, so I didn't have any classes that I had to go to. It was very difficult, but very rewarding taking care of life that is so fragile, and they became very attached to me. They were very affectionate, and bottle-fed babies tend to be the most affectionate cats, because they get so much human attention.

AM: What would you say to someone who already has a cat, but is interested in fostering? Is that something they can still do?

CB: Yeah! I have a cat that doesn't particularly like other cats or has a hard time getting used to them. I live in a very small apartment as well, so I make it work by keeping them separate for the first couple of weeks, and then slowly introducing them. Or if you have a bigger space, you can have a designated foster area, then you wouldn't have to worry about introducing them to your other animals.

AM: What is your favorite thing about fostering?

CB: Probably just knowing I've made a difference, even if it is a small difference. You have these stray animals that wouldn’t have survived that if they hadn't been brought into the shelter, especially the kittens. And so I know that we are making a small difference, and trying to limit the amount of stray cats in Baton Rouge as best as we can. But no matter how many cats and kittens we have spayed, they are always more, so there is always more to do. But yeah, I guess just making a making a little difference is what I like about it. And they're really cute!

AM: What advice would you have for people who are interested in fostering?

CB: There is a YouTuber called Hannah Shaw that has dedicated her whole life to fostering kittens. She calls herself the Kitten Lady, and she has a ton of informational YouTube videos. She's even made books on how to foster and all the different steps. So if you are interested in fostering, and are kind of nervous about starting, she has a ton of information that was super helpful to me.

Carrie and five foster kittens. Photo courtesy of Carrie Barker.

The five kittens Carrie started fostering at three weeks old. Photo courtesy of Carrie Barker.

Carrie’s cat Burma (top) and two foster kittens (middle and bottom). Photo courtesy of Carrie Barker.

A foster kitten. Photo courtesy of Carrie Barker.

Collecting Comics with Herman Mays

Herman Mays is an Associate Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Marshall University. Herman was interviewed by Mark Yeats, a Master’s student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Mark Yeats: How would you describe your research to a 5th grader?

Herman Mays: I mainly study birds. I want to know where they come from, especially birds on islands. I am curious about how they got there and how they evolved into new species. A big part of that is figuring out how many species of birds are on an island. That might seem easy, but there are some birds that are very closely related and look very similar, so you really need to dig deep to figure out if they are different species.

MY: When did you first start collecting comic books?

HM: Well, I had comic books when I was a kid in the 1970s. However, I have none of those comic books anymore! When I started in graduate school [at the University of Kentucky], I didn’t have a lot of money, but there were some great comic shops nearby. Sometimes, on my way home from leaving the lab or office, I would stop by and look at comic books, buying a few here and there. In other words, I had a few when I was in graduate school in the 90s, but I have probably been seriously collecting for only about 20 years.

MY: In total, how many comic books do you think you have in your collection?

HM: The nice thing about having collections, whether it's books or comics or anything like that, is they now have apps. For example, [Key Collector] allows you to keep track of them, so I can look and see what I have. Some people have tens of thousands, but I have 2,677. I think that's a pretty modest collection. Some people I know have around 20,000.

MY: What is the earliest comic book that you remember reading, and how do you think that influenced your interest in collecting comic books?

HM: I remember reading things like Green Lantern comics [in my early youth]. When I started collecting back in the 90s, I remember reading Venom and The Amazing Spider-Man. A more modern comic book I remember is Jason Aaron’s run on Thor. I remember that very clearly, because it dealt with issues like how there can be a loving God when there is suffering in the world. The comic book dealt with a villain who wants to kill all the gods in the Marvel universe, because of the horrible suffering his people have gone through while the gods remained silent, never helping them. I thought that was a fantastic story.

MY. What is your most cherished comic book, and what makes that one special?

HM: It was a long time ago, my wife gave it to me for my birthday or Father’s Day. She bought me The Amazing Spider-Man #31, which is the first appearance of Gwen Stacy. It's one of my oldest comic books, from 1965. It's amazing to me that you can have this seemingly flimsy paper book that’s almost 60 years old. Also, that one is great because my wife bought it for me! I think she paid $50 for it too. So not only does it have sentimental value, it is probably in my top 10 most valuable comic books.

MY: Does your interest lie mainly in the industry giants like DC and Marvel, or have you found any indie comics that you like?

HM: Most of my collection is Marvel now, and I have a few DC books but not many. However, I do have some independently published comic books. One of the new [indie] comics I have is called Animal Castle (ABLAZE Publishing). It's an adaptation of George Orwell's Animal Farm where farm animals live together in a dictatorship. I have some Image Comics, and there's one called Crossover. The premise of it is there is some weird cosmic accident and all these comic book characters that were just appearing in fiction become real and hunt down their creators.

MY: Is there any overlap between how you think as a comic book collector and a scientist? Or, has reading comic books ever shaped how you think as a researcher?

HM: The appeal of comic books is, when you're a scientist and you write a scientific paper, you are chasing after something that’s empirical. You can't make up anything. But in comic books, you can. I think part of the appeal is that comic books are not like science. Comics are so open ended.

MY: In my experience of reading comic books, I developed an interest in Alan Moore’s work. I was wondering if you have a favorite graphic novel author. What is it you find unique about their writing style or storytelling ability?

HM: I think my favorite is Frank Miller. My favorite by him, and the biggest part of my collection, is Daredevil. [During the 1980s,] Frank Miller sort of redefined Daredevil, and turned him into the version that everybody knows today. Miller writes in a very gritty, street-level setting, and Daredevil isn’t usually saving the universe like the Avengers, he is just trying to save Hell's Kitchen. He isn’t even saving New York, just his neighborhood.

MY. Is there any advice you would like to give someone interested in collecting comic books?

HM: If you have a local comic book shop, that's the best place to start. Go in and get to know the staff and tell them what sort of characters and stories you find interesting. They will be happy to help!

Herman and his son holding a few Daredevil comic books (a family favorite) that appear to be from the Bronze Age of comic books (1970-1985). Image courtesy of Herman Mays.

Herman’s office display with a wide variety of iconic comic book heroes and villains, including a Daredevil Funko Pop figure. Image courtesy of Herman Mays.

Herman’s issue of Captain America Vol 1 110 (1969), with The Incredible Hulk making an appearance. Fun fact: this story is retold from the Hulk's point of view in Savage Hulk Vol 1 1. Image courtesy of Herman Mays.

Painting with Maheshi Dassanayake

Maheshi Dassanayake is an Associate Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Louisiana State University. This interview is about her painting hobby. Maheshi was interviewed by Samadhi Wimalagunasekara, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Samadhi Wimalagunasekara: How would you describe your research to a 5th grader?

Maheshi Dassanayake: I study how plants grow in difficult environments like in deserts, in saltwater, on mountain tops, and in snow-covered regions.

SW: When did you first start painting as a hobby?

MD: I started painting after finishing high school and while waiting to start college. I was waiting until the announcement [about my college entrance exam results]. During that gap period, I didn't have much to do, and at the time I had my first boyfriend, Suniti [editor’s note: he later became her husband], so I tried to draw things to send to him. That was actually the start.

SW: Why painting? What is your favorite thing about your hobby?

MD: I always liked the natural environment and looking at paintings of birds and plants and flowers. There were leftover paints my mother had used for her work, and I simply played with that paint and started drawing or painting.

SW: Is there any specific type of painting you prefer to do?

MD: Watercolor paintings of plants and animals.

SW: Do you have any favorite paintings, and what is the story behind them?

MD: Not necessarily just one, I like a few of them. Some of these paintings are actually from one-inch postage stamps that I wanted to paint. One such stamp was a Sri Lankan stamp of the Sri Lanka White-eye, an endemic bird in Sri Lanka. Another example is the Wood White Butterfly from an Australian postal stamp. I gifted those paintings to Suniti.

SW: So, the story behind most of your paintings is just to impress Dr. Suniti?

MD: Yeah, absolutely. I was eighteen years old, and I got a new boyfriend. There was no email, SMS, or phone at the time, right? So that's what I did.

SW: Does your science help your painting or does painting help your science?

MD: There is a natural connection. I was always curious about biology. Even as a four year-old kid, when I had not formed clear thoughts about my passion for science, I was curious about pretty much every living thing. This curiosity made me pay attention to plants and animals that I could see in nature and in pictures, even in small stamps! So what I painted was an extension of that curiosity. The subjects [of the paintings] were naturally those things that I liked to see and later on studied.

SW: As a busy scientist, how do you manage time for your work and time for your hobby?

MD: I hardly have time for painting these days because I prefer to spend more time with my students in the lab. However, I plan to resume painting in the near future.

SW: Do you think it is important for scientists to have non-science hobbies?

MD: I think it's not just one hobby, scientists should have multiple non-science hobbies so that they can get a break from thinking about science and then resume science with a refreshed mindset. Everybody should have a non-science hobby.

Maheshi with one of her paintings. Image courtesy of Maheshi Dassanayake.

One of Maheshi’s postage stamp paintings: the Wood White Butterfly (Delias aganippe), a butterfly endemic to Australia. Image courtesy of Maheshi Dassanayake.

One of Maheshi’s favorite paintings, of the Sri Lanka White-eye (Zosterops ceylonensis), that she gifted to her then-boyfriend, now-husband Suniti. Image courtesy of Maheshi Dassanayake.

Lacemaking with Mary Mangan

Mary Mangan is an independent scientist and co-founder of OpenHelix, a company that provides awareness and training on open-source genomics software tools. Mary was interviewed by Garima Setia, a Master’s student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Garima Setia: How would you describe your work to a 5th grader?

Mary Mangan: The goal of my work is to help people understand where to find the [biological] data that they need and how to find it effectively. We help people get the most credible information through the best resources available. If they have had their DNA analyzed, we want them to have the best way to understand that.

GS: How did you get involved in lacemaking as a hobby?

MM: I live in Somerville Massachusetts, which played an important role in the American Revolution. I was doing volunteer work at the revolutionary war site in my city. As volunteers, we had the opportunity to walk the people through the site and teach them history about the site. During this, I became interested in learning about the clothing of the colonial period. I realized that during this revolutionary war period, lace was really important, people would put lace on their caps and cuffs. This aroused my interest in lacemaking, but I couldn't figure out how to make the lace. After doing some research, I found a local group called the New England Lace Group. They were giving an introductory workshop on lacemaking. I took the workshop and learned how to make lace. I struggled through that because making lace is complicated! Luckily the woman who taught my workshop was also interested in historic lace, and she had some extra details for me. She pointed me in a direction to find more information about the historic laces. That’s when I became interested in this particular kind of lace called Ipswich lace. This lace was made in the late 1800s, about 30 miles from me. There was this community where 600 women made lace, and I had never heard about it before.

GS: What are the things that you really love about lacemaking? And what do you find challenging about it?

MM: One of the things that I love about lacemaking is something that I didn't expect, and that is the lace culture. I didn't realize that lace would have this sort of structure around it where there are all these women who regularly meet. Every month we have lectures about the history of lace or some museum exhibit, so there's a great amount of ongoing education. If you go to a lace conference, or a lace meeting, everyone takes the workshops. People are skilling up constantly with different kinds of lace. I make a couple of kinds of lace but there are dozens of them, and people are always learning more, and they're taking another class, and they're telling you about the class. Their workshop system encourages you to skill up so much. So that was a surprise to me, and I really like that feature. What's challenging to me is how tricky some of the laces really are and it's hard to learn. Some of the patterns in the books are cryptic. They're hard to decipher unless you've taken a workshop with somebody who knows it.

GS: Are there any books you would recommend to people who want to learn lacemaking?

MM: There's a classic book by Santina Levey called “Lace: A History”. This book gives you the whole scope of lace over centuries and the different kinds of lace. This book is expensive. However, one of the cool things about lace culture is that lacemakers have their own libraries, and you can borrow the books from the library. There are also some great introductory lace books that are not too expensive, and you can buy them on Amazon. “Laces of the Ipswich” by Marta Cotterell Raffel is the one that got me into that particular historical lace.

GS: Do you think awareness regarding lacemaking is increasing nowadays?

MM: There is more awareness about lace now compared to how it was before. In the 1970s and 1980s there was a revival of interest in lace. People started coming together to form these local groups and have these workshops and conferences. Now the International Organization of Lace has small chapters, there are also many regional chapters. There is an Eastern Massachusetts lace group, that's part of the New England Lace Group. There is also a Washington DC Lace Group, Florida Lace Group, Toronto Lace Group, and upstate New York Lace Group. There is a new interest in lacemaking by some young people who are coming to lace because it is fun. A number of people do lace TikToks. There have been a couple of designs by major designers who are using handmade laces. I think it's attracting some people in new ways. So, besides the people who've been doing lace for a long time and are super knowledgeable, we've got a lot of fresh young people coming into it, too.

GS: What advice do you have for people who are interested in lacemaking?

MM: Join some local communities who are involved in it, and you will learn about it. The women who are involved in lace are eager to help! Go to Saturday or Sunday lace events, go to the demonstrations, go to the conferences and take workshops, because lace culture is super interesting. There are a whole bunch of other lacemakers who are doing lace, not in just the traditional patterns but also as art. So I would say, come into it for the hobby, and engage your brain, but also immerse yourself in the culture.

OR

Mary wearing her favorite Ipswich lace shawl at an event in Milk Row cemetery in Somerville Massachusetts. According to her, it is her best work so far, and it took her around 6 months to complete. Image courtesy of Mary Mangan.

Mary making 18th century lace and listening to 18th century music on the porch. Image courtesy of Mary Mangan.

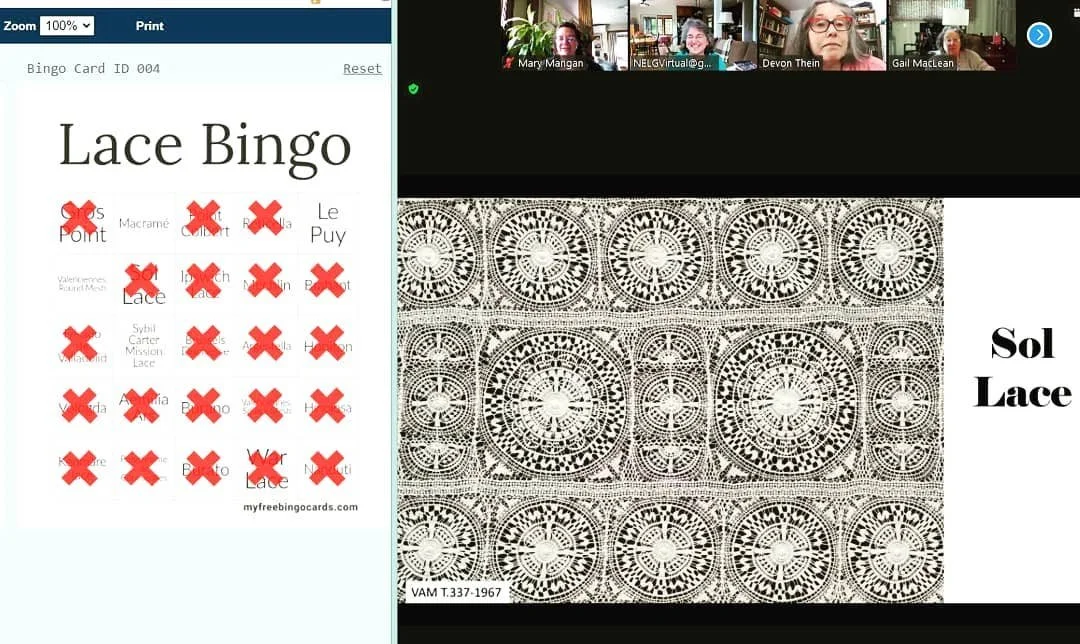

Mary enjoying “Lace Bingo” with other lacemakers at an online meeting. Image courtesy of Mary Mangan.

A silk hood with Ipswich lace made by Mary. Image courtesy of Mary Mangan.

According to Mary, the top lace is white linen, next is black silk and the yellow lace is a nod to Anne Turner. Image courtesy of Mary Mangan.

Painting with Rodrigo Diaz

Rodrigo Diaz is an Associate Professor in the Department of Entomology at LSU. This article is about his art hobby. Rodrigo was interviewed by Evelin Reyes Mendez, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Evelin Reyes Mendez: How would you describe your research to a 5th grader?

Rodrigo Diaz: I work with invasive species, organisms that come from different countries or regions and create a lot of ecological problems. People are moving goods and transporting different things faster than ever. My job is to understand how the invasive species [that are accidentally transported along with these goods] impact our ecosystem. I am very interested in finding out how species in their home countries have enemies that keep them under control; this is called biological control. One hypothesis that we are very interested in is that when invasive species arrive in a new region, they explode in number because they do not have a natural enemy. [To test this], we have different projects in different areas, in both the home countries and here. We work a lot with insects and plants that are problematic, and a lot of insecticides and herbicides are used to manage this problem. However, we may be able to use these natural enemies as an alternative method of controlling invasive species.

ERM: What hobbies do you like to do outside of work?

RD: Painting has been my hobby for so long. All of this started with my grandfather when I was a little kid. I would see him painting all the time in oil, I was mesmerized by the diversity of colors and frames [he used]. I started painting with my grandfather, and it was a great bonding time. I like that now I am doing the same with my son, and it is a great way to connect as father and son and share my love of painting and drawing with him.

ERM: Do you think this hobby makes you a better scientist, or does being a scientist make you good at this hobby?

RD: I believe it is a mix of the two. Good observation is vital both for being a scientist and for painting. I like painting insects, so I am very interested in observing proportion, colors, and features. You have seen paintings of fantastical and very realistic birds. Sometimes if I bring my [scientific perspective], I want to do a realistic representation of an animal. However, at the same time, there is a spectrum where I do not want to be super realistic; I want to lose myself a little bit and enjoy the process of creating something more abstract.

ERM: How long does it take you to complete one of your paintings?

RD: It depends on the technique I use. Some can take me eight hours and others three minutes. It also depends on if I want to do something that I can use in my science, where I need to include more details.

ERM: Do you think that having a hobby in science makes a difference in how you manage stress?

RD: Yes. Studies have shown that you have a greater capacity to concentrate at the beginning of the day: to do more analytical tasks, work on research, write a paper, and so on. However, towards the end of the day, you need to find activities that relax you more. In my case, painting is outstanding because I need to use other skill sets.

ERM: Is there any other hobby that you would like to try?

RD: In terms of art, there are other techniques that I would like to try: charcoal pencils, watercolors, and acrylics.

ERM: What advice do you have for people that are starting out painting or with their career in science?

RD: They need to put some time into developing a skill set, and the more effort you put in, the more you will start growing and enjoying the process. Science can be stressful, with [all of the] deadlines. If you start early on allocating some time for any hobby, that can help with time management. If you make time for a hobby, it will help you be more organized in general. I need to have this time for growing, not just as a scientist but as a human being. The greatest joy for me is to give my paintings away and share. I also paint t-shirts with acrylics. I put so much love into my paintings. This is my joy that I can share with friends, and maybe this sparks an interest, and they get into painting.

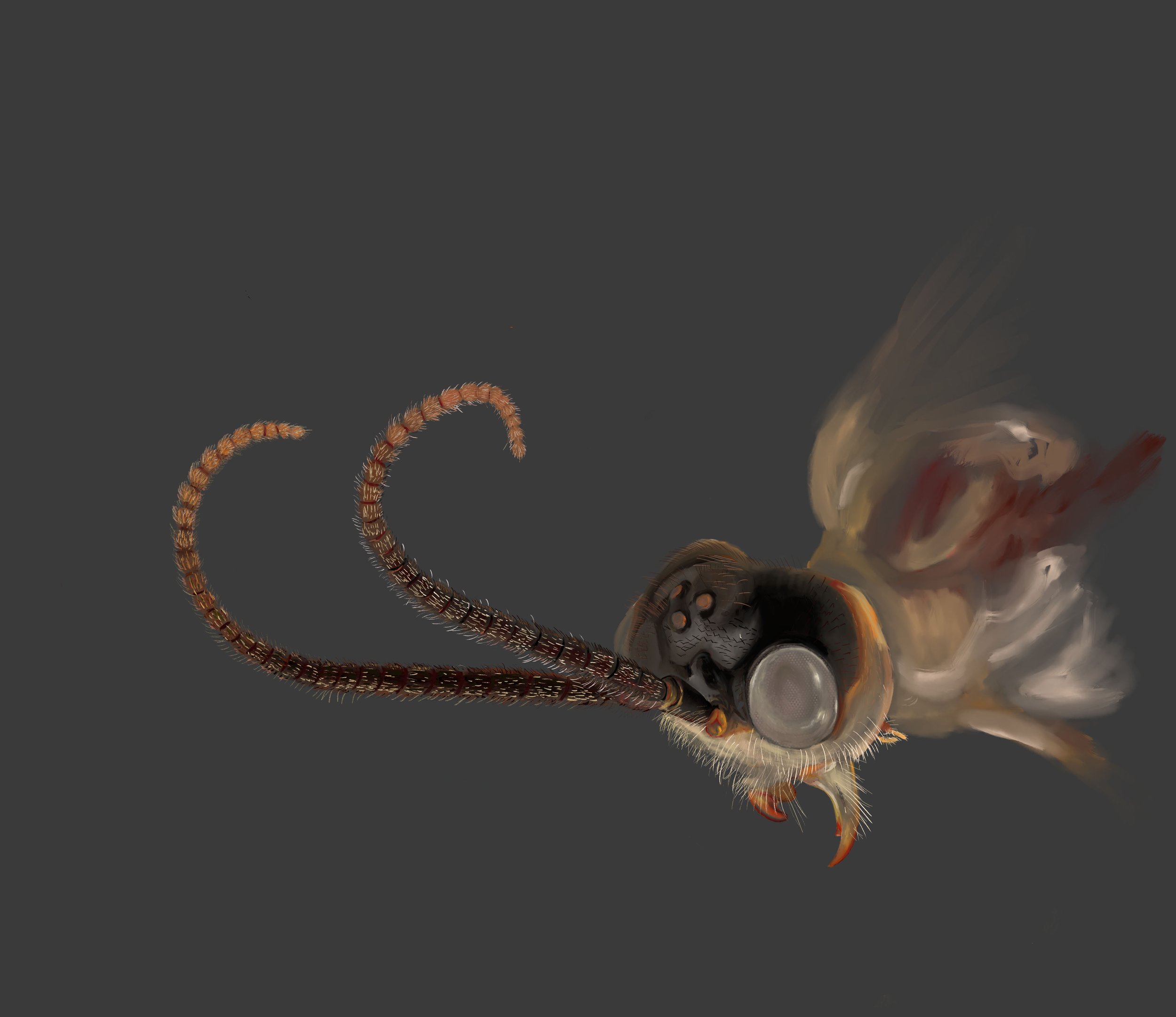

One of Rodrigo’s artworks, a close-up colorful view of an insect’s head and antennae. Image courtesy of Rodrigo Diaz.

Another of Rodrigo’s artworks, depicting a black-and-white image of a fly. Image courtesy of Rodrigo Diaz.

Rodrigo’s son also enjoys making art, as seen here. Image courtesy of Rodrigo Diaz.

Evelin had a nice time talking to Rodrigo about his art, and he kindly presented her with one of his artworks! Image courtesy of Evelin Reyes Mendez.

Scuba Diving with Maggie Knight

Maggie Knight is currently a Research Associate in the lab of Laura Basirico in the LSU College of the Coast & Environment. Maggie was interviewed by Olivia Kluchka, a PhD student at LSU. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Olivia Kluchka: How would you explain your science to a 5th grader?

Maggie Knight: As a marine ecotoxicologist, I spend a lot of time looking at chemicals in the environment and how those chemicals can potentially impact people, animals, or plants. We use a lot of technical machines to measure concentrations and presence of those chemicals.

OK: What got you into scuba diving?